Howard Johnson’s

Text and photographs copyright 8/2002 – 2007 by Glenn Wells, except as noted

For most of the twentieth century, the orange roof of Howard Johnson’s was a familiar sight along the great American roadside. When the motorist spotted a Howard Johnson’s, he knew exactly what to expect – with standardized menus and building designs, a Howard Johnson’s miles away felt as familiar and comforting as the one back home.

Howard Deering Johnson was a struggling businessman in 1925 when he put a new twist on a favorite American treat, ice cream. Using his mother’s recipe, he produced ice cream with a butterfat content far exceeding that of other brands – in essence, creating a “super-premium” ice cream years before Haagen-Dazs. After a slow start, customers flocked to Johnson’s stands at beaches along the Massachusetts shore, and Johnson kept adding new kinds of ice cream until he hit the now-familiar “28 Flavors.”

It would be the roadside restaurant, however, that would propel Howard Johnson to fame and fortune. Johnson seemed to have a keen eye for what Americans liked, and was able to combine elements of various styles of roadside dining into one package that would be appealing to the greatest number of people.

From the early days of motoring, establishments sprouted along the roadways to feed travelers, but each of these had some drawback that hindered their growth. There were tea rooms, whose homey atmosphere appealed to women, but in this era it was usually men who were driving the car. There were diners, which men liked, but women were not likely to want to sit on a counter stool in the days before booth service was common. Finally, there were hot dog stands and other casual food stops, often operating out of shacks or other unsavory looking buildings, where the quality of the food was open to question.

For his creation, Johnson borrowed a building type that was well-known and loved throughout New England: the large Colonial home. In the early years, there was some variation in the size and detailing of the buildings, partly because many of them were built by franchisees. As the 1930s came to a close, however, the style became refined and more uniform: a Colonial building sided in clapboards painted white, multi-paned windows, three dormers, and a cupola with a clock mounted on the front. This handsome style fit well in the New England towns where Johnson opened his restaurants, but Johnson added a twist of his own: a brilliant orange roof, guaranteed to catch the eye of the passing motorist. The cupola was also topped off with a weathervane featuring an outline of Simple Simon and the Pieman, a trademark developed for Howard Johnson’s by artist John Alcott.

The successful Howard Johnson’s formula consisted of more than just building design, however. Through signature menu items, Howard Johnson’s successfully cultivated an image that they were a very special place. Not only were there 28 flavors of ice cream, there was a special ice cream scoop so that all the cone servings took on a distinctive shape. Ice cream sundaes were especially large and delightful, and were topped not only with whipped cream, nuts, and a cherry, but there was also an oval shaped sugar cookie embossed with the Howard Johnson’s logo. There were “grilled in butter Frankforts” in toasted square buns served in little cardboard troughs. Fried seafood was always popular at Howard Johnson’s, especially fried clams and “all the fish you can eat” deals. And even a simple item like macaroni and cheese seemed special at Howard Johnson’s, so much so that a frozen take-home version was created, still available in supermarkets today.

Of course, not all items on the Howard Johnson’s menu were equally loved. To deal with a large menu that tried to be all things to all people, the company pioneered the concept of processing and pre-portioning food in a central commissary. This had the advantage of consistency – a Howard Johnson’s miles inland had fried clams that tasted exactly the same as at one on Cape Cod – but discerning diners could tell that the turkey dinner was turkey roll, and the mashed potatoes were the instant variety.

Another big part of the Howard Johnson mystique keyed into traveling and the open road, since their restaurants were sited primarily to serve travelers. At home, you went to a local place or ate at home. On vacation, you went to Howard Johnson’s. Thus, you could go to a HoJo’s close to home and somehow it felt as though you were on vacation.

Having built a successful business and having become a millionaire in the midst of the Great Depression, the future seemed great for Howard Johnson. By the close of the 1930s Howard Johnson’s restaurants stretched the entire length of the Eastern seaboard, from Maine to Florida. The company opened a restaurant on Queens Boulevard in New York City, reputed to have been the largest roadside restaurant at the time, to serve travelers headed for the New York World’s Fair. And Howard Johnson’s had just secured the exclusive food service contract for the new Pennsylvania Turnpike. The large travel plaza at South Midway was an immediate hit, and Sunday drivers would head on to the Turnpike just to have dinner at Midway.

World War II slowed the company for a while, as the reduction in travel brought about by the war and gasoline rationing forced most of the restaurants to close. When the war ended, however, Americans who had just been through a war and a depression celebrated the prosperous postwar years by taking to the highways. Howard Johnson’s was there to serve them.

In the booming years following World War II, the company’s strategy was to build smaller restaurants, but more of them. The familiar cupola and dormers remained, but the roofline was lower than before and had switched to a hip roof design. The modern windows on this restaurant tended to downplay the original Colonial style just a bit.

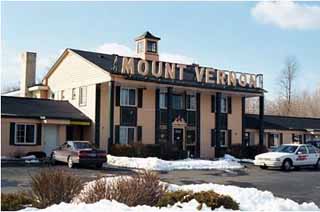

Meanwhile, many motel operators in the postwar years were finding that a great location was right next door to a Howard Johnson’s restaurant. Throughout the automobile age, “Gas – Food – Lodging” have been the three necessities of travelers and it has always made sense to group them together. Savvy motel operators played off the highly regarded Howard Johnson’s name by copying some of their Colonial style elements such as white clapboards and roof cupolas. The motel’s name often reinforced the connection to Howard Johnson’s with names such as “Mount Vernon” or “Landmark Motor Lodge” which was inspired by the Howard Johnson’s slogan “Landmark for Hungry Americans.”

The Mount Vernon Motel in East Greenbush, NY was built next to Howard Johnson’s and copied its Colonial styling. Later on, the motel even copied the “environmental” color scheme adopted by Howard Johnson’s in the 1970s. (2002 photo. The motel is still open but has been renamed America’s Best Value Inn.)

The success of many of these motels did not go unnoticed by Howard Johnson’s. The company decided to enter the lodging business, opening the first Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge in Savannah, Georgia in 1954. The building design was strikingly similar to the Mount Vernon Motel pictured above, but added a red brick facade to the Colonial with cupola style. Savannah, Georgia was also a great overnight stop to serve the Northeasterners who knew and loved Howard Johnson’s best as they journeyed to Florida.

Meanwhile, the construction of new toll highways continued at a rapid pace in the postwar era. Following the success of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, new toll roads were opened in other states, including New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Indiana. The other toll roads copied the Pennsylvania concept of service plazas right on the highway, and Howard Johnson’s successfully bid on the rights to operate the restaurants in many of them. This proved to be a winning strategy for the company, positioning the company name alongside the forces of modernity and progress. Howard Johnson’s successfully promoted the idea that as you were driving the new, modern highways, you should dine at a new, modern Howard Johnson’s restaurant.

Colonial architecture seemed a little incongruous for a company promoting newness and modernity, however, and the company was rapidly expanding into other parts of the country where the design seemed out of place. Therefore, the new restaurants followed a prototype designed by Rufus Nims featuring a hip roof with a wide overhang and no dormers (still brilliant orange, of course) and much larger plate glass windows, running floor to ceiling in the counter area. Clapboards gave way to stucco, but the restaurant was still painted white. The cupola design went through several variations in the 1950s before settling on a design with fins at the base topped by a sleek turquoise pyramid with a Simple Simon and Pieman weathervane.

The Howard Johnson’s in Greenfield, Massachusetts (left) made it to 2002 with perfectly intact 1960s styling, save for the fact that the cupola fins were repainted “environmental” brown in the 1970s. Sadly, this gem has given way to an Applebee’s. (2001 photo)

The cupola at the Lake George, NY Howard Johnson’s shows the Simple Simon and Pieman weathervane. (2001 photo)

In 1956, President Dwight Eisenhower signed legislation authorizing a system of Interstate highways, and America started its greatest road building frenzy to date. The federal legislation set specific design standards that the states must follow to receive federal funding, and one of them prohibited the kind of service plazas that had proved lucrative for Howard Johnson’s on toll highways. But, rather than having their growth slowed, the company acquired real estate directly off the exit ramps, and frequently the parcels were large enough to include a Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge as well as a restaurant. The old real estate axiom, “Location, location, location” summed up the company’s mode of operation, and in the early days only gasoline stations were as aggressive as Howard Johnson’s in snapping up choice parcels at the exits of the new Interstate highways.

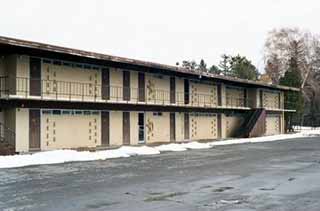

Host of the highways: These orange roofs sprouted at Exit 6 of the new Adirondack Northway (Interstate 87) in Latham, NY soon after it opened in the late 1950s. The Howard Johnson’s Restaurant logged nearly forty years in business before closing in 1995; the motor lodge succumbed two years later and both of these buildings were demolished. Today, a Bennigan’s stands on the site of the restaurant; the remodeled motor lodge is now a Quality Inn. (1997 photos)

The Simple Simon and the Pieman logo was created by artist John Alcott in the 1930s and the design was replicated countless times on signs, menus, and china patterns. Adding the town name above the logo next to the entrance gave a sense of place to a restaurant that looked identical to hundreds of others across the country. Most of these were removed during 1970s remodelings, but this one in Greenfield, Massachusetts survived until 2002. (2001 photo)

Whether out of Yankee thrift or reverence for the past, the older Colonial style Howard Johnson’s buildings continued in business with most of their original styling intact, including the dormers and traditional cupola. However, the entryways were frequently remodeled in a style matching that of the new restaurants. The stone wall to the left of the entry of the East Greenbush Howard Johnson’s (later Weathervane Seafoods) once had a Simple Simon and Pieman similar to the one in Greenfield. (2002 photo)

)

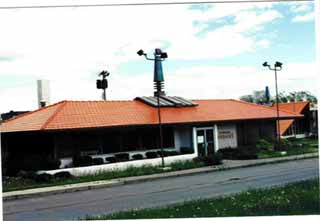

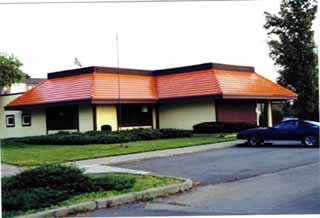

Four views of the Howard Johnson’s Restaurant and Motor Lodge at New York Thruway Exit 23 in Albany: The lodge building above retains its original styling, but is presently unused and deteriorating. Below left, the restaurant is intact but closed and it is doubtful that it will ever reopen as a Howard Johnson’s. Below right, the original motor lodge gatehouse remains in place behind an add-on stucco facade. The original orange roof tiles remain in place, and you can see the spot on the ridge where the cupola used to be.

UPDATE: Today, this motor lodge is no longer part of the Howard Johnson chain. The still-closed orange roofed restaurant (below left) remains in place and the gatehouse (below right) has been re-roofed in a different color. (2002 photos)

As the company entered the 1960s, the company had a successful formula in place, and there were plenty of new Interstate highways being built providing prime locations for Howard Johnson’s Restaurants and Motor Lodges for years to come. The company went public, and Howard D. Johnson passed control of the company to his son, Howard B. Johnson.

In the mid 1960s, Howard Johnson’s was at the top of its game. In 1965, the company’s sales exceeded that of McDonald’s, Burger King, and Kentucky Fried Chicken combined. However, a few small leaks were beginning to develop in that brilliant orange roof.

In 1965, Howard Johnson’s introduced the “Concept 65” restaurant, intended for high volume locations. A second gable was added to the front of the building, resulting in a T shaped floor plan. The rest rooms were to the immediate right of the entryway. This restaurant opened in Plattsburgh, New York when the Adirondack Northway (Interstate 87) was completed in the late 1960s. Other Concept 65 restaurants were located in Glens Falls, NY and Nashua, New Hampshire. (1996 photo. Today this is a 99 Restaurant.)

Social critics of the 1960s were questioning the conformity of the 1950s, and a large chain of lookalike restaurants proved an easy target. In the early days, Howard Johnson’s sameness was seen as an improvement over the wildly inconsistent roadside food offerings of the day, but by now it was seen by many as bland and dull.

The younger Howard Johnson assumed control of a company that had become large in a relatively short time, and lines of supervision were not always clearly drawn. In the early days, Howard D. Johnson would often pay surprise visits to his restaurants to make sure his standards were being kept, but the chain had grown so large that this was no longer possible. Also, most Howard Johnson’s restaurants drew their customer base off the highway rather than local repeat business, so this gave some of the less scrupulous operators cover to let the standards slip. But, as more and more travelers experienced mediocre meals in deteriorating surroundings served by indifferent help, ultimately this cost the company.

As more of the Interstate Highway system neared completion and the nation became saturated with orange roofs, the company looked to other restaurant concepts for continued growth, tacitly admitting that maybe the Howard Johnson’s restaurant was not all things to all people. Red Coach Grill, an upscale steakhouse similar to the Steak and Ale chain, was often located next to a Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge to tap business travelers and their expense accounts, but ultimately the concept did little for the company. More successful was the Ground Round, a casual restaurant chain that survives today under separate ownership.

One restaurant segment that saw phenomenal growth in the 1960s went little noticed by the company: fast food. The company assumed that the traditional Howard Johnson’s Restaurant would remain the standard in roadside dining even as McDonald’s and their imitators added locations at a rapid pace. Even traditional rival Marriott Corporation, whose Hot Shoppes restaurants competed with Howard Johnson’s in some places, entered the fast food segment with its Roy Rogers chain.

When Howard D. Johnson died in 1972, his name was a well-established brand, and the restaurants and motor lodges he left behind enjoyed a healthy business, even if they were not everybody’s favorite place. Some big changes were just around the bend, however.

One of the biggest changes was increased competition. When many of the Interstate highways first opened, Howard Johnson’s was the only restaurant at the interchange. By now, dozens of restaurant and fast food chains had staked their claim off the exit ramps. The old Howard Johnson’s concept of all things for all people was challenged by a new era of specialization, as new restaurant chains with limited menus promised food that was better, faster, and cheaper than what you got at Ho Jo’s. As the 1970s progressed, the Howard Johnson’s menu continued little changed, except that high inflation caused prices to rise. Many young families found that they could stop at McDonald’s instead, the kids liked it, it took less time, and it cost far less. The customer base at Howard Johnson’s, meanwhile, was becoming older and grayer, the same people who had made the chain a success in its earlier years.

In the 1970s, when orange roofs already stretched from coast to coast, the few new restaurants that were built followed a new design. Young Howard Johnson had more of a reputation as a cost-cutter than an innovator, and this boxy design with fewer windows reflects the new need for energy conservation. The soaring rooflines and visual fronts of the stylish earlier designs were gone. The exterior colors were also changed to “environmental” tan and brown, and the earlier white restaurants were repainted to match. This restaurant along a new section of Interstate 90 in East Greenbush, New York opened in 1978, closed in 1995, and today it’s a Denny’s. (1997 photo)

In 1980, Howard Johnson’s was sold to the Imperial Group, a British concern. Imperial continued to operate the still-large chain of restaurants and hotels with few changes. But, with the Interstate Highway System largely complete, the opening of new Howard Johnson’s restaurants all but stopped. In fact, many existing HoJo’s sought greater fortunes in converting to the company’s newer Ground Round casual restaurant concept, or by painting over the orange roof and going independent.

Howard Johnson’s was no longer alone on the commercial strips at highway interchanges, and appeared to be slowly losing the battle for traveler’s road food dollars. However, on the older toll highways that preceded the Interstates, it seemed as though things hadn’t changed since the 1950s. Howard Johnson’s enjoyed exclusive long-term contracts to operate the restaurants on many of these highways, and the traditional HoJo’s with counter and booth service still ruled the toll road, although some locations had cafeteria lines for quicker service. This, too, was about to change.

The original 1940 contract that had granted Howard Johnson’s the exclusive right to operate restaurants on the Pennsylvania Turnpike had come up for renewal. The Turnpike Commission used this opportunity to bring fast food chains to the Turnpike on a trial basis, and they were an immediate success. Seeing the handwriting on the wall, Howard Johnson’s secured the franchise rights to Burger King on toll highways, and former HoJo locations on roads such as the New York Thruway and Massachusetts Turnpike became Burger Kings.

In the mid 1980s, the Howard Johnson’s logo was redesigned, tossing aside the distinctive Howard Johnson’s lettering for simple block letters proclaiming “HOWARD JOHNSON.” The apostrophe-S was inexplicably deleted. But the biggest change of all came shortly afterward in 1985, when the Imperial Group sold the assets of the Howard Johnson Company, except for the Ground Round chain, to Marriott Corporation.

Unlike the Imperial Group, Marriott had little interest in maintaining Howard Johnson’s the way it was. The Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodges did not fit Marriott’s more upscale image in the lodging business, so they were sold to Prime Motor Inns. The lodging chain kept the Howard Johnson name, and continues today as a unit of Wyndham Worldwide. A new logo was unveiled in 1997, keeping familiar blue and orange colors but putting the Howard Johnson name in script-like lettering. Most interestingly, the top of a dormer peeks out above the name, a subtle nod to the chain’s early three-dormer restaurant style.

Logos through the years: The one at left represented the chain through its glory years and into the 1980s. The center one dropped the apostrophe-S and was used by the lodging chain until 1997. At right is the Howard Johnson’s Restaurant logo adopted by Franchise Associates.

Possibly the portion of Howard Johnson’s of most interest to Marriott was their toll road food service operations. Marriott was already a big player in this field, and folding the Howard Johnson’s operations into their own created an industry giant. Travel Plaza by Marriott (later Host Marriott) operated some locations under the Howard Johnson’s name for a while, but eventually all were remodeled and by the 1990s the Howard Johnson’s name had disappeared from toll highways. The Howard Johnson’s acquisition also enabled Marriott to add Burger King to a growing stable of brands it operated on toll roads, including Big Boy, Roy Rogers, and Sbarro.

Marriott had similar intentions for the remaining Howard Johnson’s Restaurants, wanting to convert them to Big Boy rather than continue the Howard Johnson’s brand. This plan met with resistance from many Howard Johnson’s franchisees, who had built their reputation on HoJo’s (and likely did not want to incur the remodeling costs of switching to another restaurant brand.) The franchisees formed a new company, Franchise Associates, and successfully acquired from Marriott the rights to the Howard Johnson’s restaurant business, including the trademarks, recipes, and rights to sell Howard Johnson’s food products, such as ice cream and macaroni and cheese.

Franchise Associates made one notable attempt to create a Howard Johnson’s of the future: a new prototype restaurant in Canton, Massachusetts. Rather than an all-new structure, this was a remodeling of an existing Howard Johnson’s of the ranch house style typical in the 1950s and 1960s. Among the new design features was a modernistic arch over the entrance with the Franchise Associates Howard Johnson’s logo prominently displayed. Also, half of the legendary orange roof was changed to gray and the cupola was removed. The overall effect was unsettling to those who love traditional Howard Johnson’s styling, and the prototype did little to reverse the decline of the chain. It closed in 2000. (Photograph courtesy of Rich Kummerlowe)

Franchise Associates brought a familiar logo out of retirement to represent their organization: Simple Simon and the Pieman, which had been around since the 1930s but retired in the 1970s. And at the restaurants themselves, there were hopeful signs that things were moving in the right direction. As restaurants came up for repainting, many locations ditched the dreadful tan and brown “environmental” colors imposed in the 1970s and went back to the original white with turquoise trim. Inside, nostalgia was the drawing card: the menu covers featured images from HoJo’s glorious past such as the 1939 World’s Fair “World’s Largest Restaurant,” and ice cream was promoted with signs proclaiming, “Tastes as good as you remember!”

Amid the hopeful signs were signs of trouble, though. Franchise Associates seemingly did little to actively promote the Howard Johnson’s brand or add new locations while the restaurant business became increasingly competitive. Meanwhile, the existing Howard Johnson’s Restaurants were aging, and sometimes not very gracefully. If somebody remodeled a Howard Johnson’s, chances are it was to convert it to a Denny’s or some other restaurant brand. Others simply closed and were demolished or converted to non-restaurant uses.

As of 2005, what little that remained of the Howard Johnson’s Restaurant chain went into free fall. That year brought a slew of closings, including restaurants in Millington, Maryland and Bay City, Michigan. Franchise Associates itself ceased to exist when the last restaurant it owned, located in Springfield, Vermont, was closed and demolished. The landmark Howard Johnson’s in New York City’s Times Square, a holdover from the “old” Times Square, was also closed forever.

With the failure of Franchise Associates, the rights to Howard Johnson’s Restaurants reverted to Howard Johnson International, the parent company for the Howard Johnson hotels and inns. In March 2006, the food and beverage rights to the Howard Johnson name were licensed to La Mancha Group, LLC. A re-launch of the Howard Johnson’s brand was promised, but it never materialized. The owners of the Waterbury, Connecticut Howard Johnson’s chose to separate from the chain, cutting the number of operating restaurants to a mere three. When the Lake George Howard Johnson’s failed to open for the 2012 summer season, the number of operating restaurants dropped to two.

The year 2014 marked the 60th anniversary of Howard Johnson hotels, but in truth there wasn’t all that much to celebrate. Today Howard Johnson hotels are lost among the many low end hotel brands controlled by Wyndham – Days Inn, Super 8, Microtel, and Knights Inn among them – and many operating Howard Johnson properties are merely a rebrand of a hotel built for another chain. The original motor lodges with their distinctive design have succumbed to age, remodeling, and often demolition. Wyndham is promising a “brand refresh” and occasionally will release something cool to keep Ho Jo fans interested. Will there be a brand refresh, and will it succeed? Only time will tell.

Meanwhile, the remaining Howard Johnson’s Restaurants went under one by one. The Lake Placid restaurant closed in 2015, followed by Bangor in 2016. The Lake George Howard Johnson’s reopened after having been closed for three years, but the operation was erratic and many visitors reported it barely resembled a classic Howard Johnson’s. By 2022 the last Howard Johnson’s Restaurant in the world was closed as well.

For more on Howard Johnson’s, visit:

America’s Landmark: Under the Orange Roof by Rich Kummerlowe

HoJo Land by Walter Mann

Photos from Ho Jo’s first decade: Howard Johnson’s Connection to Nahant

“Howard Johnson” trademarks are the property of Howard Johnson International.

This is an unofficial web page. All trademarks referenced therein remain the property of the trademark owners.