Diner FAQs

What’s a “Diner?”

Everyone would agree that a diner is a specific type of restaurant with qualities that make it different from any other. In almost all instances, a diner has counter service, basic American fare at reasonable prices, and breakfast available anytime the diner is open. Given their roots serving

factory shift workers, diners have traditionally been open around the clock, but as the economy has changed, many diners are now open only for breakfast and lunch.

To the diner purist, the diner building itself is important. According to the strictest definition, a “diner” means only a prefabricated structure built in a factory by a diner manufacturer and then moved to its destination in a section or sections. However, many establishments using the word “Diner” were actually constructed on-site in the same manner as conventional buildings. On-site diners, often referred to as homemade diners, sometimes resemble factory-built diners, sometimes they do not.

According to a RoadsideFans poll conducted in 2001, two-thirds of the respondents were willing to consider on-site buildings diners, so long as they followed diner styles and intentions. The remaining third was split evenly between those who feel only factory-built units qualify as diners and those who consider anyplace that calls itself a “diner” to be a diner regardless of its building or styling.

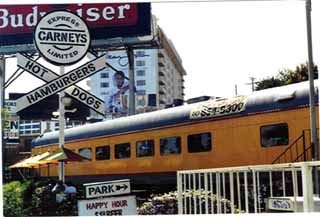

Diners are old railroad cars, aren’t they?

In nearly all cases, no! This myth seems to have great staying power with the general public. It’s true that many older diners resemble railroad or trolley cars, but if you saw a diner and railroad car side by side, you’d see that they’re different. In a few cases, old railroad or trolley cars were converted into diners, but often the conversion had a homemade look and sometimes these places had an unsavory reputation compared to diners crafted by the diner manufacturers.

Birdseye Diner (Silk City), Castleton, VT DINER |

Carney’s, Sunset Strip, Los Angeles, CA RAILROAD CAR |

Some people refer to a diner as a “hash house” or a “greasy spoon.” Does this mean the food is bad?

Let’s be honest for a minute. If every diner from the beginning of time had been spotlessly clean and served delicious food, such terms never would have entered the vocabulary. Some diners DO serve food deserving of the epithets that some people hurl at ALL diners. But diners are hardly alone in serving sub-par food. Even some very high priced restaurants can turn out some meals that are less than satisfactory. Then, of course, there are the fast food chains, where the fare is more consistent from

location to location, but that does not mean that it is good.

Mike Engle has a good theory regarding eating at a diner versus a fast food place. If you stop at a fast food restaurant, there is a 100% chance you aren’t going to like it. At a diner, maybe the food will be bad, but maybe it will be wonderful. So even if there’s only a 50-50 chance you’ll like your meal you still have better odds than with fast food.

What’s an “environmental” diner?

It’s a diner whose styling follows the “Environmental Look, ” as defined by Chester Liebs in his book Main Street to Miracle Mile. By the mid-1960s, social critics, including First Lady Lady Bird Johnson, were taking aim at roadside architecture, and flashy, neon-trimmed, stainless steel diners which were regarded as modern a mere decade earlier were suddenly out of date. The diner manufacturers responded with designs that reflected a new styling ethic thought to be more environmentally friendly: brick or stone facings, mansard roofs, and little or no stainless steel. Often, environmental diners follow a styling theme such as Colonial or Mediterranean.

I’ve seen diners like that. Aren’t they site-built structures?

Not necessarily. From their early days as lunch wagons with only a few stools inside, diners have grown steadily larger. The earliest diners were shipped as a single unit with cooking done behind the counter. Later ones were still a single unit, but cooking was moved to a rear kitchen. This was often site-built of wood or concrete block, or sometimes an old diner on the site was reused as the kitchen for the new one. Beginning after World War II, multi-section construction techniques were perfected, allowing diners to expand with virtually no limits. Thus, the large mansard roofed place shares a common heritage with the old single unit diner. It’s just that it arrived on its site in multiple sections that were then re-assembled.

How can I tell if a diner is built on-site or by a diner manufacturer?

The definitive way is to find a tag, but since so many diners have their tags missing, you need to look for other clues. Factory built diners often have windows, curved sections, or elaborate stainless steel work rarely duplicated by local tradespeople building a site-built diner. Another clue: Factory built diners are set on a foundation, much like a house. That means you have to go up a few steps (or a ramp) to get inside. On-site diners are often built on a slab, as are stores and other commercial buildings, with no steps.

What’s a “Tag?”

A tag from a Silk City diner, Uncle Milty’s Glenmont Diner in Glenmont, NY, serial number 3671. (Photo: Gregg Anderson)

The “Tag” is the diner manufacturer’s identification plate, customarily installed on all newly manufactured diners. It includes the manufacturer’s name and address, and sometimes a serial number or company slogan. Usually the tag is mounted over the front entrance, in the vestibule, or over another doorway such as the kitchen or rest room doors. Sometimes a diner will have more than one tag, mounted over multiple doorways. Many factory-built diners have no tag at all because it was removed in a remodeling, and at times one manufacturer would remodel a diner originally built by another, replacing the original tag with one of their own.

Why is it important to know who manufactured the diner?

Easiest answer I can think of: If you like cars, you care whether it’s a Ford or a Chevrolet, don’t you?

Did all diner manufacturers use serial numbers?

No. Some of the manufacturers who used serial numbers include Mountain View, Silk City, Sterling, Swingle, and Worcester, but even with these companies the serial number did not always appear on the tag.

Do the serial numbers follow any kind of system?

Often yes, and at other times it can get confusing. Here’s what’s known about diner serial numbers:

Mountain View diners feature sequentially numbered tags. Most of the existing Mountain Views have three digit serial numbers with 3 or 4 as the first digit.

Silk City used a system combining the last two digits of the year with the sequence number for that year. For example, the Martindale Chief Diner, Silk City # 5807, is the seventh diner built in 1958. Some Silk City serial numbers have five digits, indicating years in which more than 100 diners were built! However, from 1960 until the company’s closing in 1964, the numbering system changed to one where all the serial numbers end in 71.

Sterling serial numbers combine the year and sequence number, similar to Silk City, except that they did not use leading zeroes so some serial numbers are three digits. The Wellsboro Diner in Wellsboro, Pennsylvania is Sterling serial number 388, the eighth diner built in 1938

Swingle diner serial numbers contain the last two digits of the year built in the last two digits of the serial number. This is followed by a combination of the letter suffixes D, K, and V, standing for “Diner,” “Kitchen,” and “Vestibule.” The Country View Diner, east of Troy, NY, is a 1988 diner, serial number 488DKV, indicating the job consisted of a diner, kitchen, and vestibule. (This diner was later renovated by DeRaffele.) Serial numbers do not appear on Swingle diner tags.

Worcester started with serial number 200 (figuring buyers would be wary of serial number 1) and numbered all their diners consecutively up to serial number 850 (Bobby’s Girl Diner in New Hampshire.)

I often see letters after a diner’s name, such as Birdseye Diner(SC). What does this mean?

It is an abbreviation for that diner’s manufacturer, as listed in the table below. For clarity, only the most popular makes of currently existing diners are shown.

Examples:

Birdseye Diner(SC) is a Silk City diner.

Rosie’s Diner(P) is a Paramount diner.

Pronunciation Guide:

DeRaffele: de-RAF-uh-lee Fodero: fo-DAIR-oh

| Manufacturer | Company name and address | In business | |

| B | Bixler | Bixler Manufacturing, Norwalk, OH | 1931-1937? |

| C | Comac | Comac, Irvington, NJ | 1947-1951? |

| D | DeRaffele | DeRaffele Manufacturing, New Rochelle, NY | 1933-present |

| DM | Diner-Mite | Diner-Mite Diners, Atlanta, GA | 1959-present |

| F | Fodero (note 1) | Fodero Dining Car Company, Bloomfield, NJ | 1933-1981 |

| K | Kullman | Kullman Industries, Lebanon, NJ | 1927-2011 |

| M | Master | Master Diners, Pequannock, NJ | 1947-mid 1950s |

| MV | Mountain View | Mountain View Diners, Singac, NJ | 1939-1957 |

| O | O’Mahony | Jerry O’Mahony, Inc, Elizabeth, NJ | 1913-1956 |

| OS | On-site | Diner constructed on-site | |

| P | Paramount | Paramount Modular Concepts, Oakland, NJ | 1932-present |

| S | Sterling | J. B. Judkins Company, Merrimac, MA | 1936-1942 |

| SC | Silk City | Paterson Vehicle Co, Paterson, NJ | 1927-1964 |

| ST | Starlite (note 2) | Starlite Diners, Ormond Beach, FL | 1992-2006 |

| SW | Swingle | Swingle Diners, Middlesex, NJ | 1957-1988 |

| V | Valentine | Valentine Manufacturing, Wichita, KS | 1938-1974 |

| W | Worcester | Worcester Lunch Car Co, Worcester, MA | 1906-1961 |

| WD | Ward and Dickinson | Ward and Dickinson, Silver Creek, NY | 1923-1940? |

Note 1: Fodero was known as National Dining Car Company starting in 1939. Production resumed after World War II under the Fodero name.

Note 2: Starlite was known as Valiant Diner Company beginning in 2002.

Manufacturer addresses and years of operation are from American Diner Then and Now by Richard J. S. Gutman, updated as necessary

The manufacturer abbreviations are based on a system used by Roadside Magazine in the 1990s.